Chronic illness may result in gradual or sudden sensory changes in vision, hearing, taste and smell, as well as in the sense of touch and proprioception (i.e., sense of body position).

Most individuals rely heavily on the sense of vision to complete daily tasks. It is essential for reading, recognizing others and interpreting facial expressions.

Vision change is common in a wide range of chronic illness. In multiple sclerosis, changes may fluctuate from day to day, or be more noticeable at certain times of day or when fatigued. Visual changes can also appear gradually over time. The most common changes in vision result in the following:

- Blurry vision or the inability to focus on a target

- Moving the eyes in an uncoordinated manner

- Repeatedly gazing back and forth between two places

- Difficulty following a moving target (i.e., visual pursuit)

- Reduction or absence of visual fields (e.g., tunnel vision, gaps in central vision or peripheral vision).

Individuals with gaps in the central part of their visual field (as often happens with age-related macular degeneration) often find that they see best when they look at a target with their eyes and/or their head held in a certain position.

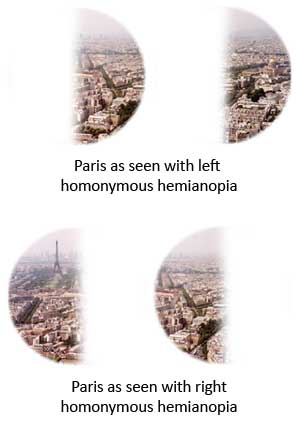

Homonymous Hemianopia

Following a stroke or brain injury, some people see only what

is on the right or on the left side of the visual field, a condition known as homonymous hemianopia. Each eye only sees what is in half the visual field. It is like having masking tape put over the left (or right) half of each lens of your

glasses. Individuals with this condition only see part of what is in front of them and, as a result, are likely to be unsafe driving, crossing a street, operating power tools or cooking.

Following a stroke or brain injury, some people see only what

is on the right or on the left side of the visual field, a condition known as homonymous hemianopia. Each eye only sees what is in half the visual field. It is like having masking tape put over the left (or right) half of each lens of your

glasses. Individuals with this condition only see part of what is in front of them and, as a result, are likely to be unsafe driving, crossing a street, operating power tools or cooking.

Caregivers can help loved ones compensate for this condition with the following strategies:

- Encourage the person to turn their head to the affected side to increase the amount seen.

- Remind the person to check and double-check the affected side (e.g., “look to the left” or touch their left arm).

- Jointly identify and practise compensating strategies in a variety of situations.

- Place commonly used items in view on the unaffected side, especially items needed for safety (e.g., phone, mobility aids).

- Keep important items in one location so there is no need for the person to search.

- Remove items that may cause tripping.

- Mark door frames with brightly coloured tape to prevent bumps and bruises.

- Draw a line (or hold a ruler) along the left margin to act as a starting place for writing or reading.

Neglect

Another perceptual problem that may result from a stroke or brain injury is a decreased awareness of one side of the visual field, a condition called neglect. In addition to vision, touch and hearing may also be affected. You may notice that the person:

- Eats only from one side of the plate

- Has difficulty finding objects

- Is unaware of people and objects on the affected side, including not hearing them speak

- Bumps into door frames

- Trips over obstacles that should have been noticed and avoided

- When reading, loses their place, skips words, or reads only one side of a menu

- Dresses only one side of their body

- Puts make-up on only half of the face

- Has difficulty with reading, writing and arithmetic

- Gets lost because they only make turns toward the unaffected side

Individuals with neglect should avoid the same activities as people with homonymous hemianopia. Many of the same compensating strategies are also beneficial.

Nystagmus

Nystagmus is an involuntary eye movement that causes the eyes to flick back

and forth between two points. It may or may not affect vision, depending on where it occurs in the range of motion of the eyes. If it is present with the eyes in a midline position, vision will be affected. If it is only present at the outer or inner

limit, it may not significantly affect vision.

Nystagmus is an involuntary eye movement that causes the eyes to flick back

and forth between two points. It may or may not affect vision, depending on where it occurs in the range of motion of the eyes. If it is present with the eyes in a midline position, vision will be affected. If it is only present at the outer or inner

limit, it may not significantly affect vision.

Assistive Devices or Adaptations

Depending on the particular vision problem, assistive devices or adaptations may be able to compensate for the limitation. These include large numbers on phones and other control devices, written materials with large print or alternative formats (e.g., audiobooks), and digital audio recorders. Individuals may be better able to operate devices with relatively smooth control surfaces (such as a microwave oven) if a square of masking tape or other textured surface is affixed to the “start” button.

The sense of touch may be altered in a

variety of ways. There may be a sensation of “pins and needles” or numbness, which can increase risk of falls and injury. Individuals may lose the ability to discriminate temperature, which can result in a much higher risk of injury due to burns.

A person may also be hypersensitive making touch very uncomfortable. Altered sensation can cause challenges that are surprising for many because there may be few visible signs, but it may be nearly impossible to complete daily tasks independently.

The sense of touch may be altered in a

variety of ways. There may be a sensation of “pins and needles” or numbness, which can increase risk of falls and injury. Individuals may lose the ability to discriminate temperature, which can result in a much higher risk of injury due to burns.

A person may also be hypersensitive making touch very uncomfortable. Altered sensation can cause challenges that are surprising for many because there may be few visible signs, but it may be nearly impossible to complete daily tasks independently.

Caregivers may need to support the individual to use other senses to provide alternate methods of making discriminations that would normally be done by touch. For example, sight may compensation for touch in some instances. Instead of feeling the way to the washroom at night, it may be necessary for loved ones to turn on a light and look where they are going. Thermo-sensitive crystal-based thermometers can be used to identify the temperature of a surface, such as a stove or radiator, rather than risking a burn. Surfaces that are normally smooth can be roughened with sandpaper to make them easier to feel.

Most hearing aids are now designed to adjust the amplification at different

frequencies, so conversations are far easier to follow than the uniformly amplifying hearing aids of the past.

Most hearing aids are now designed to adjust the amplification at different

frequencies, so conversations are far easier to follow than the uniformly amplifying hearing aids of the past.

Using a telephone is particularly challenging for people with a hearing impairment. If your loved one has trouble hearing on the phone, there are a number of amplified telephones available from telephone stores. Some are designed to work with hearing aids and some amplify the incoming sound. Alarm clocks and door bells are available that use lights instead of tones to attract attention.

Telephone devices and services for the deaf often use a keyboard and text over the phone lines. Many in the deaf community now use Skype™ or Apple’s FaceTime™ to establish a visual connection and use sign language to communicate with other deaf people. These methods of communication can also be helpful for individuals who supplement their residual hearing with lip reading.