The roots of the word “cognition” are from the ancient Greek,

cogito, which means to think or to know. You may be familiar with the phrase from Rene Descartes, a famous 15th century scholar, “Cogito ergo sum” (i.e., “I think therefore I am”), which illustrates the superiority of the intellect over

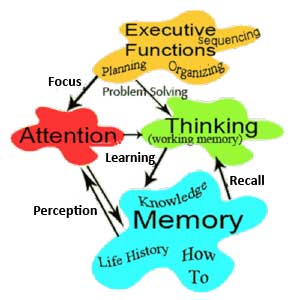

other functions. Although cognition translates roughly as “to know,” a number of different interconnected abilities go into the process of knowing. We will focus on four elements that, working together, account for a lot of what we do: executive functions,

attention, thinking and memory.

The roots of the word “cognition” are from the ancient Greek,

cogito, which means to think or to know. You may be familiar with the phrase from Rene Descartes, a famous 15th century scholar, “Cogito ergo sum” (i.e., “I think therefore I am”), which illustrates the superiority of the intellect over

other functions. Although cognition translates roughly as “to know,” a number of different interconnected abilities go into the process of knowing. We will focus on four elements that, working together, account for a lot of what we do: executive functions,

attention, thinking and memory.

In the best of circumstances, the integrated nature of our cognitive functions helps us function well at work, at home and all the places in between. It is only when a chronic disability disrupts one or more of these cognitive functions that we become aware of the important role they play in day-to-day life.

Executive functions help us initiate

activity and organize what we do. Executive functions tell our senses what to focus on in order to process information, solve a problem or carry out a physical task. Like other mammals, humans are “hard-wired” to notice changes in our surroundings

(e.g., changes at the edge of an area, movement). But we can also intentionally shift our attention and focus on other elements of the environment.

Executive functions help us initiate

activity and organize what we do. Executive functions tell our senses what to focus on in order to process information, solve a problem or carry out a physical task. Like other mammals, humans are “hard-wired” to notice changes in our surroundings

(e.g., changes at the edge of an area, movement). But we can also intentionally shift our attention and focus on other elements of the environment.

Executive functions also help us plan what to think about in order to solve a problem or ensure that we do things in the proper order. For instance, the executive part of the brain will direct the thinking part to draw the instructions from memory for how to do laundry in the proper sequence to ensure clothes are cleaned correctly.

Retrieving information from memory

Retrieving information from memory is another cognitive ability. We do not have to recall when and/or where we learned something in order to retrieve and use a particular piece of knowledge, although if we are having difficulty remembering a fact, we may try to recall the circumstances in which we learned it or last thought about it as a way to retrieve it. Or if we are trying to retrieve a word that is on the tip of the tongue, we can cue ourselves by trying to identify the first letter or other words that it sounds like. Or if we forget where we were in a procedure, we may go back to the physical location where we last knew what we were doing to try to get back on track. These strategies are examples of executive functions.

In information processing, attention

is necessary to recognize and label sensory input. Attention draws on knowledge in memory to interpret or make sense of what we see, hear, feel, smell or taste. This interpretive process is called perception, which is a basic form of comprehension.

In information processing, attention

is necessary to recognize and label sensory input. Attention draws on knowledge in memory to interpret or make sense of what we see, hear, feel, smell or taste. This interpretive process is called perception, which is a basic form of comprehension.

Thinking

Working memory (also called short-term memory) is what most people describe as thinking. We can only think about a limited number of things at a time, and we only have a short time to bring something back for further thought once we stop thinking about it - unless we have stored it more permanently in memory.

We usually talk about the process of storing something

in memory as learning and the process of retrieving it from memory as recall. Not everything we think about gets learned. We may think about a math problem and calculate it in our head without creating a memory of that event. On the

other hand, if it is a new type of math problem that we will need in future, we may think about it in ways that help us learn that math procedure. In general, the more we make connections in our thoughts between a new piece of information and things

we already know or have experienced, the more likely we are to learn and be able to recall it when needed and produce an appropriate response.

We usually talk about the process of storing something

in memory as learning and the process of retrieving it from memory as recall. Not everything we think about gets learned. We may think about a math problem and calculate it in our head without creating a memory of that event. On the

other hand, if it is a new type of math problem that we will need in future, we may think about it in ways that help us learn that math procedure. In general, the more we make connections in our thoughts between a new piece of information and things

we already know or have experienced, the more likely we are to learn and be able to recall it when needed and produce an appropriate response.

Memory (also called long-term memory) is where we store all kinds of information that helps us live successfully in the world. We all have personal memories of things that have happened, places we have been and people we have known. Some memories are more vivid than others. Other memories represent our store of knowledge - rules of language and meanings of words, facts and other types of general information we have learned. There are various types or forms of knowledge; for example, one type is procedural knowledge, or how to do things, based on previous learning and our personal experience.