How Shirley Became a Caregiver

A map is useful at the start to help prepare for

the journey. It provides suggestions for the best routes to take. Along the way, a map tells you how far you've come and how far you still have to go.

A map is useful at the start to help prepare for

the journey. It provides suggestions for the best routes to take. Along the way, a map tells you how far you've come and how far you still have to go.

- If the path you have chosen is slow going or blocked, the map provides alternative routes. But a map is only a tool; you still make the choices.

- Your choices affect not only you, but your travelling companion and the other passengers who join the voyage. And like any journey involving others, negotiation is involved to ensure that everyone’s needs are met as well as possible, including your own.

This module describes the role of the family caregiver and why caregiving is important, common illnesses or chronic disabilities that require caregiving, the changing needs of the person requiring care, and caregiver reactions to chronic disability.

Caregivers provide ongoing informal and unpaid personal

care. They provide support to another person who lives with challenges due to a disability, an illness, an injury and/or aging. The supported person may be a spouse or life partner, a parent, another family member (e.g., sibling, aunt,

uncle or grandparent), an adult child or a close friend. The supported person may live in the same household or elsewhere.

Caregivers provide ongoing informal and unpaid personal

care. They provide support to another person who lives with challenges due to a disability, an illness, an injury and/or aging. The supported person may be a spouse or life partner, a parent, another family member (e.g., sibling, aunt,

uncle or grandparent), an adult child or a close friend. The supported person may live in the same household or elsewhere.

While most people think of caregiving in terms of addressing the physical or medical needs of a loved one, caregiving also addresses the person’s emotional and cognitive needs. Cognitive (or intellectual) needs may include help with learning, remembering, thinking things through and problem solving.

The Caregiver—A Pillar of Strength

The caregiver has many roles. At times, caregivers act as partners to their loved one, liaisons with professionals and as advocates. They also serve as nurses, teachers, counsellors, chauffeurs and cheerleaders. While fulfilling these roles, caregivers are also dealing with their own emotions about the situation, the physical impacts of caregiving on their health and the social effects on relationships with other family members and friends. There may be financial burdens as well.

It’s not easy being the designated “pillar of strength.” Yet, there are also rewards, including a sense of purpose, strengthened bonds with your loved one, personal growth, and greater knowledge and problem solving skills. You will also make new friends in support groups and community programs who understand what you are going through and encourage you.

It’s not easy being the designated “pillar of strength.” Yet, there are also rewards, including a sense of purpose, strengthened bonds with your loved one, personal growth, and greater knowledge and problem solving skills. You will also make new friends in support groups and community programs who understand what you are going through and encourage you.

This course will give you two types of tools to succeed in caregiving and deal with the stresses involved.

- The first set of tools consists of knowledge and strategies to manage caregiving challenges. These tools can help you reduce the stressors that often arise in caregiving.

- The second set of tools is made up of effective coping mechanisms for dealing with stress and for maintaining your own physical, mental, emotional and spiritual health.

I have the right:

I have the right:

- To take care of myself. This is not an act of selfishness. It will give me the capability of taking better care of my loved one.

- To seek help from others even though my loved one may object. I recognize the limits of my own endurance and strength.

- To maintain facets of my own life that do not include the person I provide care for, just as I would if he or she were healthy. I know that I do everything I can for this person and I have the right to do some things just for myself.

- To get angry, be depressed and express other difficult feelings occasionally.

- To reject any attempt by my loved one [either conscious or unconscious] to manipulate me through guilt, anger or depression.

- To receive consideration, affection, forgiveness and acceptance for what I do for my loved one for as long as I offer these qualities in return.

- To take pride in what I am accomplishing and to applaud the courage it has sometimes taken to meet the needs of my loved one.

- To protect my individuality and my right to make a life for myself that will sustain me in the time when my loved one no longer needs my full time help.

- To expect and demand that as new strides are made in finding resources to aid physically/ mentally challenged and ill persons in our country, similar strides will be made toward aiding and supporting caregivers.

Caregivers’ contributions are vital to our health care system. Caregivers provide transportation to appointments, arrange for medical devices and aids, pick up prescriptions, select home care providers and fulfill many other roles.

Caregivers’ contributions are vital to our health care system. Caregivers provide transportation to appointments, arrange for medical devices and aids, pick up prescriptions, select home care providers and fulfill many other roles.

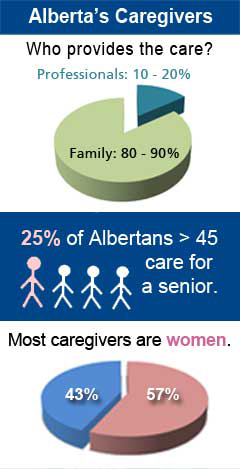

- Family caregivers provide 80 - 90% of the care needed by people with chronic conditions.

- More than half a million people in Alberta are caregivers for a senior or someone with a chronic disability.

- In 2007, one in four Albertans over the age of 45 was reported to be caring for a senior. (This does not include those caring for younger individuals.)

- In Canada, about 57% of caregivers over the age of 45 were women.

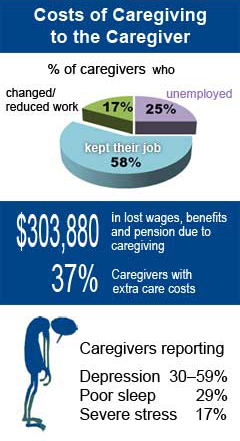

The Costs of Caregiving

Caregiving is costly to the caregiver. Approximately 75% of caregivers were employed while providing care, with 15 – 19% changing or reducing paid work to accommodate caregiving. About 37% reported extra care costs. In 2011, the average caregiver over the age of 50 could be expected to lose nearly $304,000 in wages, benefits and future pensions due to caregiving responsibilities.

In addition to financial costs, caregivers incur personal costs. About one in six caregivers experience “severe stress,” with nearly 56% reporting difficulties with emotional demands, stress, fatigue, and lack of time for themselves. Caregivers are at increased risk for diabetes, hypertension, depression, pulmonary disease and kidney disease. Sleep disturbances are noted by 29%, and 30 – 59% report symptoms of depression.